GDT Nature Photographer of the Year 2025

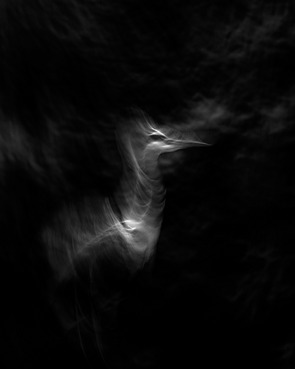

Overall Winner: Konrad Wothe - Dipper flying through waterfall

It’s been over 20 years since I first witnessed a dipper darting through a waterfall. The small passerine bird was flying back and forth to a nest tucked away safely behind a dense curtain of water. Of course, back then I was desperate to capture the moment on film, but with the analogue gear of the time, there was simply no way to freeze this spectacular split-second moment in sharp focus.

Then, two years ago, I had the good fortune to encounter another dipper nesting behind a waterfall—this one also regularly shot through the curtain of water. Interestingly, the bird alternated between the wet approach and flying around to the side of the waterfall. Armed with cutting-edge digital gear and ultra-fast cameras, I felt I might have a chance of capturing this curious behaviour.

Even so, the challenge remained immense: there was no predicting exactly when the dipper would leave its nest and dive through the waterfall, nor could I pinpoint the exact spot where it would emerge. Frustratingly, the bird didn’t always follow the same path. Thanks to the new pre-burst mode on my camera, capturing the bird in frame wasn’t difficult. Still, getting the correct focus and perfect composition took thousands of exposures.

On top of that, the bird's wing position wasn’t always ideal. I lost count of the number of trips I took to the dipper's nesting site before I was reasonably satisfied with the result. And even now, I keep going back — and always will — because the dipper is one of my absolute favourite birds.

About Konrad Wothe

A sense of freedom and lightness, a curiosity and spirit of discovery, and a profound urge to be one with nature, far from the hustle and bustle of modern life and within grasp of the heartbeat of life itself. It is this that forever draws Konrad Wothe into the woods both near and far. And it is these emotions and experiences that infuse his images and stories, enabling them to enchant audiences and transport viewers into distant realms.

Born in 1952, Konrad Wothe started taking photographs at the age of eight. After finishing high school, he worked as a cameraman for the legendary Heinz Sielmann. He then went on to study biology and produce wildlife documentaries for ZDF together with his fellow student Michael Herzog. For over 40 years, Wothe has worked as a freelance nature photographer and wildlife filmmaker. His work has received numerous awards.

A deep love of nature has taken Konrad Wothe to some of the most spectacular and remote places on Earth — from the Arctic to the Antarctic. To this day, his focus remains squarely on nature and wildlife with the aim of sharing the beauty and wonder he experiences with as wide an audience as possible. Just as importantly, he seeks to heighten awareness for our collective responsibility toward the environment. His powerful and unforgettable multimedia presentations allow audiences to share in his most striking and exhilarating encounters with the natural world.

Wothe's multimedia presentation Fascination Rainforest showcases a cross-section of this work and highlights some of his most fascinating jungle adventures.

Konrad Wothe is a member of the German Society for Nature Photography (GDT) and the Gesellschaft für Bild und Vortrag e.V. (GBV).

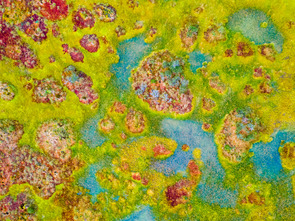

Special Category: Both eerie and beautiful - Germany‘s Peatlands and Bogs

Foreword by the patron of the Special Category - Prof. em Dr. Michael Succow

It is both a pleasure and an honour to act as patron of this prestigious competition. Exactly 40 years ago, in the spring of 1985, I wrote the following sentence in the foreword to my book about Germany's peatlands, Moore in der Landschaft":

“Anyone who starts to explore the natural world and encounters healthy peatlands will be captivated by the magic of these habitats and inspired to return time and time again. The peatlands of Central Europe are among our very last semi-natural landscapes.” The photographers whose work appears in this category have undoubtedly felt this beckoning: their images vividly portray the extraordinary variety of peatlands, their abundance of life, and also the mystical aspects that fascinates so many of us.

My enthusiasm for peatlands dates back to my biology degree in the 1960s. Over the intervening decades, however, it has become painfully clear that only a fraction of Germany’s former peatland diversity survives. Today, more than 95% of our peatlands have been drained. It is therefore essential to raise awareness of the pivotal ecological role of bogs, moors and mires; and to restore damaged peatlands through rewetting. In the context of today’s human-induced climate crisis, the significance of peat is at last being recognised: healthy, growing peatlands are long-term carbon stores and sinks. In Germany, these habitats lock in some 1.2 billion tonnes of carbon—the nation’s largest terrestrial carbon sink. Drained peatlands, by contrast, release CO₂ and account for over 7% of Germany’s total greenhouse gas emissions.

Fortunately, the importance of peatlands is now widely appreciated in Germany. Numerous conservation programmes are under way in peat-rich states, and the federal government’s Climate Action Programme identifies healthy peatlands as both carbon sinks and refuges for unique plant and animal assemblages.

The alliance between nature and photography can help inspire many more people to appreciate peatlands as unique and valuable ecosystems in need of protection. The photographs submitted to the German Society for Nature Photography’s competition highlight our Earth’s beauty, diversity and fragility. These images speak to a growing audience of concerned citizens who are motivated to look more closely, desire to understand in greater detail, and are ready to act. Our future depends on what we do—now.

This in mind, I wish the competition, with its long tradition and influence far beyond Germany, success in the years ahead. I am particularly delighted by this special category, which places peatlands centre stage. We need more wet peatlands!—for climate, biodiversity, flood protection, and, quite simply, as magnificent landscapes.

Professor Emeritus Dr Michael Succow

Patron

Recipient of the Right Livelihood Award 1997, Founder of the Michael Succow Foundation

About Prof. em Dr. Michael Succow

Michael Succow was born on 21 April 1941 into a farming family in eastern Brandenburg, Germany. As a child, he tended the family’s sheep and began recording his wildlife observations at the tender age of twelve. During his years at school, he developed a profound love of the natural world and forged a friendship with the Kretschmann family, pioneers of nature conservation in East Germany.

Succow studied biology at the University of Greifswald (1960–1965), where he wrote a diplom thesis on peatlands and married Ulla, a fellow student and microbiologist. He then became a research assistant at the Institute of Botany and worked on his PhD dissertation entitled Genesis and vegetation of peatlands in Western Pomeranian river valleys and their anthropogenic transformation.

In the wake of the Prague Spring, Succow was obliged to leave academia in 1969 and prove himself a valuable member of society while working as a site surveyor for the state melioration combine in Bad Freienwalde until 1973. Nevertheless, he completed his doctorate in 1970 and served as a researcher at the Academy of Agricultural Sciences of the GDR from 1974 to 1989. While keeping below the political radar, he wrote a habilitation thesis on Landscape-ecological classification and typology of GDR peatlands. Despite multiple requests, he was denied the opportunity to return to the university.

During the German transition period in January 1990, members of the citizens’ movement pressed for Succow’s appointment as deputy minister responsible for natural resource protection and land use planning in the restructured Ministry of the Environment. In this position, he worked together with trusted colleagues to designate vast protected areas within the boundaries of the former GDR. In March 1990, almost 12% of the GDR's territory was provisionally given protected status - half of which was written into law after reunification. Many consider this „the" coup of German Unity.

Succow left the ministry at his own request in May 1990 and briefly worked as visiting professor in applied ecology at the Technical University Berlin. During this period, he united German conservationists from the East and West within the newly founded NABU (Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union) and later served as its vice president.

In autumn 1992, Michael Succow was appointed professor of geobotany and landscape ecology and director of the botany institute and the botanical garden at the University of Greifswald. He held these posts until his retirement in 2006. Thereafter, he devoted much of his time to national and international conservation initiatives via the Michael Succow Foundation which he established in 1999 using the prize money from his Right Livelihood Award (“Alternative Nobel Prize”). The foundation implements projects on four continents in the fields of climate protection, protected area management, sustainable land use and nature talent traineeships, and is a partner of the Greifswald Mire Centre.

Photo: Stefan Schwill

Prize of the Jury

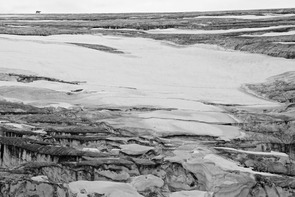

Prize of the Jury | Levi Fitze (DE) | Patterns in the snow

Prize of the Jury | Levi Fitze (DE) | Patterns in the snow

Jury 2025

Peter Lindel

Peter Lindel has been taking photos of anything he can get his hands on since the age of 14. However, his enthusiasm for animals began in childhood: two animals from the children's cosmos every evening, read aloud by his father - just as analogue as the photography back then. He has been a serious nature photographer for around 20 years and his focus is clearly on mammals. His photographic work - or rather pleasure - can best be divided into ‘Dortmund’ and ‘elsewhere’. He would describe himself as a classic animal photographer, if this category still applies today. If the result and the experience are equally satisfying, then it was a nature photography day for Peter that he remembers fondly. The different approaches and image styles of the many nature photographers are what make it interesting for him to look at their pictures and certainly not the fact that they may have the same focus as he does.

Many of his pictures have won awards in prestigious photography competitions, including Wildlife Photographer of the Year. In 2020, he was named GDT Nature Photographer of the Year.

Melanie Arndt

Melanie Arndt has a degree in biology and began taking nature photographs during her studies. Her interests range from macro to landscape photography, whereby she mainly captures impressions from her travels. Her projects have taken her from Tasmania to the Falkland Islands, from sub-zero temperatures in Iceland's winter to the heat of the Costa Rican jungle. Her work is partly documentary, to show animals and plants in their ecosystem, but also abstract - in an attempt to convey a feeling for the moment.

Thomas Scheffel

Even as a child, Thomas Scheffel was magically drawn to nature. His native Rheinhessen was a small world waiting to be discovered. From his early youth, he discovered photography as a medium for preserving his experiences. Now he has been on this path for over 30 years and the world has become bigger and bigger. After travelling extensively, his photographic focus is still on his immediate surroundings. The fascination of seeing familiar things in a new way and turning them into pictures is what drives him time and again. Nature photography has become the guiding principle of his life, albeit not professionally. His pictures are intended to inspire the viewer with a personal perspective and convey connections. For Thomas, travelling in nature is a way of better understanding many things. Although the image remains the great driving force for him, it is no longer mandatory. The realisation that ‘bigger, faster, further’ is not his goal is the essence of his long journey in nature photography. Creative perspectives, special moments and the simple, clear beauty of nature guide his design.