Winner: Jasper Doest - Netherlands

Dutch photographer Jasper Doest creates visual stories that illuminate the diverse relationships between humans and nature. As a trained ecologist, Doest knows that human life depends on everything our planet has to offer and that humanity's current consumption patterns are unsustainable in the long run. Doest strongly believes in the power of photography to effect change, and he is a Senior Fellow of the International League of Conservation Photographers and an Ambassador for the World Wildlife Fund. His awards include four World Press Photo Awards, and in 2020 he was named European Nature Photographer of the Year. His work appears regularly in National Geographic magazine.

Project: Nsenene

Twice a year, after the rains in Uganda, countless grasshoppers or bush crickets of the species Ruspolia differens appear, forming huge swarms at night in search of food and breeding partners. During this time, a lot of people in rural areas stay up until dusk to catch and sell the insects, which are called nsenene in Ugandan. This is an old tradition in Uganda that creates jobs and provides considerable income, as the crickets are considered a delicacy and are highly sought after.

Predicting the Ugandan grasshopper season is a risky venture for people trying to make money in this country of widespread poverty. But many are willing to take the risk. In addition, people involved in nsenene harvesting are at risk of long‑term damage to their health from prolonged exposure to UV-C radiation from the bright lights used to attract the animals. Catching crickets is opportunistic, just like the citizens of Uganda, and the business of nsenenes has grown rapidly in recent years as a result of the country's economic boom. At the same time, climate change, deforestation, palm oil plantations and the use of pesticides on farms threaten the insect's habitat and challenge the future of this fragile ecosystem and its traditions.

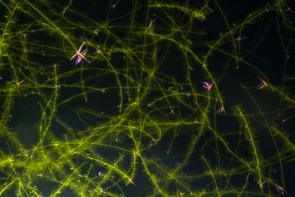

Nsenene | 1

Swarming crickets or katydid, called nsenene in Uganda, over a commercial harvest site where light and smoke are used to attract and stun the insects intended for human consumption.

Nsenene | 2

Ruspolia differens is an economically relevant cricket species in East Africa, where there are specific markets for the distribution of these insects. They are rich in proteins, essential fatty acids, vitamins and minerals. Commercial breeding of these animals could help to improve food security in the region, generate income for locals and conserve wild populations in the long term.

Nsenene | 3

On a cloudy morning in Ntoroko, children help carry the metal sheets and barrels used for catching the nsenene during the night. In return, they are allowed to collect the crickets that remain from the catch and sell them at the local market.

Nsenene | 4

The Katwe market in Kampala is the most important trading place for nsenene in Uganda, where the animals are sold to local vendors. People from all over the country arrive here with their vans at sunrise to be the first to sell the freshly caught insects, which are still alive at that time and stored in large bags.

Nsenene | 5

Since the 1990s, the nsenene harvest twice a year has become a vital business for an increasing number of Ugandans. It provides jobs for countless people: from those who catch them to those who sell them to those who prepare them. It allows debts to be paid off and school fees to be paid. But in recent years, with a changing environment and a growing number of people competing for the same catch, it has become increasingly difficult to make a profit.

Nsenene | 6

Around four o'clock in the morning, Muntadhar Nasif looks at some of the nsenene he caught while helping an acquaintance with the harvest. Nasif used to catch nsenene as a little boy when they were still abundant during the rainy season. Today, with less nsenene around, Nasif – who enjoys a stable income as a tour guide – thinks it’s too much of a gamble to invest in the nsenene business. However, many young people change jobs temporarily to have a go at this potentially profitable venture.

Nsenene | 7

A man replaces a light in his nsenene harvest system. Heat and brightness attract these night flying insects. Therefore, the glowing spirals of 400-watt halogen lamps are used. These are connected to several chokes to increase their output to 1200 watts per lamp. With daily operation, such a lamp lasts for only about a week. Power consumption is registered, although some installations also illegally tap into the power grid.

Nsenene | 8

In the past, the nsenene were collected by hand, an activity carried out by women and children, although only men would eat them. It was traditional for women to collect nsenene for their husbands and receive new gomasi (traditional dresses for women in Uganda) in return. The more nsenene a woman collected, the better or more beautiful the gomasi she received from her husband.

Children helped their mothers collect the crickets during the season. When there was no trade in these insects, women and children made an effort to collect enough insects for the father of the family. However, nsenene were exchanged between male relatives on the basis of reciprocity, which fostered and strengthened social ties and networks.

Then, in the mid-1990s, some Masaka residents had the idea of using powerful electric lamps as traps, which attracted huge swarms of nsenene and created a new source of income. Today, the trade in these insects has become lucrative, and men and women are now equally involved in collecting and selling them.

Nsenene | 9

Nsenene trapped in an old oil drum try to escape. When in the mid-1990s some Masaka residents had the idea of attracting the insects with strong electric lights, such barrels filled up quickly. Today, they remain almost empty throughout the night. Uganda's wetlands, the nsenene's main egg-laying habitat, have shrunk by more than 40 % since 1994. And near Masaka, sand pits, rice fields and settlement areas have gradually encroached on the surrounding wetlands.

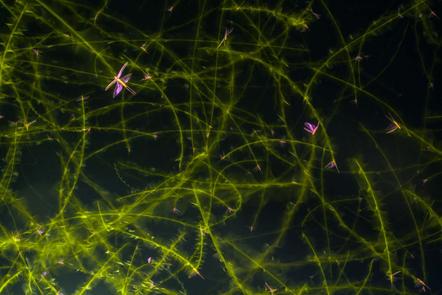

Nsenene | 10

Night view of a combination of individual harvest facilities. Over time, people have discovered that the greater brightness and warmth emitted by their combined facilities increases the chances of attracting swarming crickets.

As the number of harvesters in Uganda continues to rise and more and more harvest facilities compete for the same prey, the chances of making money during the season are diminishing. The boom in commercial harvest facilities, in addition to the ongoing changes of climate and habitats of the nsenene, also poses the risk of over-exploitation of the species. Scientists are now looking at breeding nsenene to reduce the pressure on the ecosystem without losing any market potential.